Risk, Delay, and some Theory

Current graduate student, Kelli Johnson, and former graduate student, Michael Bixter, have published an article in Judgement and Decision Making. The paper reports a meta-analysis of published associations between intertemporal preferences (involving delayed rewards) and risk preferences (involving risky rewards). Results suggest an association that is consistently non-zero, but too weak to provide any support for existing theories. You can read the article itself for more details. But here, I wish to use this study to highlight a broader issue.

Multiple theories, from multiple disciplines, have proposed that delay and risk influence behavior through a single, common mechanism, what we call single-process theories. The most intuitive of these (my personal opinion) suggests that delay necessarily implies risk. Imagine that I offer to give you $100. Is it more plausible that you will receive this money if I am due to pay you in a week or if I am due to pay you in 3 years? Presumably there are a number of things that could prevent repayment: I could lose your money in Vegas, I could pocket your money and skip town, the stock market could crash and I could lose all of my (and your) money, I could become ill, incapacitated, or even die. Presumably each of these potential impediments becomes more probable as the delay period is prolonged: delay necessarily entails risk [1].

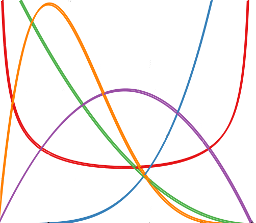

According to this theory, intertemporal choices (e.g., $50 today or $100 in 2 weeks) ought to involve the same mechanisms responsible for risky choices (e.g., betting on a coin flip). How does one evaluate such a theory? In the studies we meta-analyzed, researchers had participants make a bunch of intertemporal choices and also make a bunch of risky choices. Preferences in each task were quantified and associations between the individual differences observed in each of the two tasks were evaluated. In common practice, significant, non-zero associations are taken as evidence supporting the single-process accounts and non-significant associations are taken as evidence against the single-process accounts. Easy!

The problem, however, is that “significant association between individual differences” isn’t a prediction clearly made that any of the single-process theories. At best, it’s an indirect implication that one can draw once a slew of additional assumptions are added into the mix. For example, even if delay entails risk, one needs to specify exactly how these quantities are related before knowing how preferences should be related (e.g., Sozou, 1998; Dasgupta & Maskin, 2005). It is extremely unlikely that any specification would yield a straightfoward, linear relationship which complicates predictions. Furthermore, different decision makers may hold different beliefs about the relationship between delay and risk, complicating the interpretation of individual differences. All in all, if you sit down to read the original theoretical proposals and try to work out exactly what constraints they place on the empirically observed associations, you’d likely come up empty.

So why do researchers interpret the associations in such a simplistic fashion? Part of it is presumably that it’s just simpler to deal with “theory predicts association” than it is to engage with the all the pesky details that need to be confronted when diving into the actual (albeit under-specified) theory. This is an unfortunate, but seems to resonate with recent comments from other researchers (in very different research settings).

For example, Eiko Fried (2020) argues that researchers often conflate theoretical models and the statistical models we use to evaluate those theories. Tal Yarkoni (2019) recently wrote the following:

It is not simply a matter of researchers slightly overselling their conclusions here and there; the fundamental problem is that, on close examination, a huge proportion of the verbal claims made in empirical psychology articles turn out to have very little relationship with the statistical quantities they putatively draw their support from.

That sounds bad! Though both of these researchers are discussing somewhat different concerns, you can see very similar theoretical slippage arising in the context of the studies we meta-analyzed. Single-process theories make claims about decision-specific processes and at least insuinuate quantitative rigor. But researchers often (always) boil all this down into a new pseudo-theory that simple says “risk-delay correlation > 0” [2].

It is an understatement to say that these sorts of simplificaitons reflect lazy thinking. The broader problem, however, is that the literature is littered with empirical findings that, collectively, appear to represent scientific progress but actually mean very little. As we make clear in the paper, the empirical data is not good for the single-process theories typically implicated, but it’s also not good evidence against these theories (or any others). It’s a big pile of mush and I think we can do better.

So yeah. I think the take-home messages are:

- Be thoughtful when connecting theories to empirical predictions.

- Assume that these connections are more complicated than you’d hope (Jolly & Chang, 2019).

- Distinguish between the statistical model used to evaluate predictions from the theory that predicted those predictions.

Notes

[1] We once submitted a manuscript (Bixter & Luhmann, 2015) and one of the reviewers suggested that we simply explain to participants that the delayed rewards (e.g., $100 to be delivered in a month) were to be treated as certain; that they were guaranteed to be received. But how could such a guarantee be given? And why would a participant accept such a guarantee?

[2] Don’t even get me started on “impulsivity”.

References

Dasgupta, P., & Maskin, E. (2005). Uncertainty and hyperbolic discounting. American Economic Review, 95(4), 1290-1299.

Sozou, P. D. (1998). On hyperbolic discounting and uncertain hazard rates. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 265(1409), 2015-2020.

Yarkoni, T. (2019, November 22). The Generalizability Crisis.